This is Torsten Janson’s report from his research stay in Jerusalem in the fall 2023:

The utter irony. Chased by a deadline, I spend my first days by the iPad. The occasional break for tea and dried prunes down Salah ad-Din Street. A quick stop to see Anna Hjälm and the STI staff. But mostly: frantic writing at the Albright Institute. Submitted. Pfeew. Tomorrow: a day in field. Finally, it begins!

Did it ever.

Just after daybreak in the freshness of the summer-warm morning. October 7. I find my way to the obscure monument over Palestinian and Jordanian soldiers fallen in the war of 1967, just north of the City Walls. An hour of photographing among weeds and plastic bottles in this remote lieu de memoir that no one seems to remember. Attempting to decipher the faint inscriptions on shattered, depilated gravestones. Who is remembered here? Who remembers? Whom does memory serve?

Off again along the road beneath Mount Olive. Towards Silwan, one of many sites of conflicted space and memory in the city. An ancient Palestinian neighbourhood threatened by the incursion of the massive City of David excavations. Houses shattering from underground drillings. Evictions and house demolitions. The violence, contest, and clashes of space, memory and culture in an occupied city.

At that moment: blaring sirens.

I stop and gaze and listen. Eastern Jerusalem stretches out before me beyond the busy road. Sheikh Jarrah, Wadi al-Joz. The silhouette of Hebrew University on top of the ridge. An extended wail rolling down the hill sides. This is not the police. Nor fire brigades or a burglar alarm. Trouble in the settlements? On a Saturday morning? Yet all is quiet beyond the stream of traffic, in uncanny contrast with the sound of emergency. I make a quick recording and resolves to move on.

Video recording of the first rocket alert in the city, on Derekh Yerikokh, Eastern City, 7 October 2023.

I continue by the Jewish cemetery with eyes on the stupefying vista over the Kidron Valley, the Ottoman walls, the Dome glistening in the morning sun. Qubbat al-Sakra. The Temple Mount. Moria. The pure exhilaration of being here.

The day is already heating up. With pleasure I enter the shade of the narrow alleys of Silwan, aimlessly wandering up and down paths and stairways among Hajj-decorated walls. And a second blare of sirens shatters the morning stillness. What is happening?

‘Sabah al-kheir!’ The men quietly chatting outside a tiny food shack turn around to scrutinise me sceptically. Someone murmurs a reluctant good morning. ‘Are you lost?’ I have only begun a stuttering answer when he interrupts. ‘It is trouble today.’ ‘Trouble?’ ‘Yes, trouble in Gaza.’ ‘What is going on?’ Shrugs. ‘There will be police. Maybe not to go into the village.’ ‘No maybe not. Have a good day.’

The uncanny feeling is slowly turning into something else, something with a taste of metal. I should not be here. Determined to walk calmly, my heart beats harder than the stairs warrant. Something is happening. Again: blaring sirens. And now a ripping, cracking bang. Distant yet physical. A sound like textile violently torn. Like thunder in a clear blue sky. Like something very, very wrong.

Palestinian Silwan, Eastern City, with buildings adorned with Pilgrimage insignia, 7 October 2023.

Down the valley and up the Old City by the Western Wall, always patrolled by police. But today things are different. Groups of 8 or 10 uniformed youth punctuate street in intervals. Like units mobilized. Fences block the road down towards the City of David. A uniformed girl with her hands on the AK wave me off: that way! The road up along the Wall. My steps are faster now.

Outside Zion Gate. Sirens. Renewed explosions. And only now I see it: white streaks criss-crossing the southern sky, ending in puffs. Moments later: a sickening bang.

Thirty minutes later I am back by Albright on Salah al-Din. Here the atmosphere is different. People stand in groups in corners, outside the stores and cafés, eyes in the sky. There! Another one! Occasional cheers. I exchange words here and there. ‘It is Gaza. They are shooting back.’

The following week is a blur of memory fragments. Hours on end reading news, communicating with colleagues and friends, re-assuring the family. Yes, all is ok. I agree with my children to post a frog-emoji every morning to indicate I am safe. It somehow becomes a reassuring ritual of conjured control and routine. As rituals are prone to be.

But things are not ok. Gradually the extent of the horror of October 7 dawns upon us. Israeli media overflows with reports on the attack, with calls for retaliation and war. And with it comes the fear of what will be next, in Gaza, on the West Bank. How will Israel respond? How bad will it be? The answer is immediate as bombs begin to fall over Gaza.

The city comes to a stand-still, holding its breath. What now? Will the Palestinian neighbourhoods explode? Occasional rocket fire from Gaza prompts me to download a security alert app to my mobile. Albright Institute empties out. I spend largely sleepless nights in my make-shift shelter, away from windows. In the streets, the presence of military and police is suffocating. No rallies, no burning waste bins, no calls for intifada. Damascus Gate is sealed for Palestinians, blocking passage into the Old City for prayer and manifestations. A longstanding hotspot of gatherings and demonstrations becomes an assembly point for listless journalists.

With gratitude I accept the invitation to move up to STI, where I remain for the following months. Here too visits and classes are cancelled. The charming Beit Tabor is empty – but not inactive. Under Anna’s coordination, STI becomes a sanctuary for local activism and deliberation between Israeli, Palestinian, Jewish, Muslim, Christian organisations. (Without my next-to-daily conversations with you, Anna, without your insight, care, unsentimental passion, humour and commitment, I doubt I would have stayed.)

Am I scared? Yes and no. I feel bizarrely secure in the centre of the city. And the security itself becomes sickening. Who can feel safe in a state of atrocity? I am torn between rage and relief. Between guilt and gratitude. Fear and fury incapsulates me, dissolving the line between the sanctuary of my room and the horror transpiring a mere 400 kilometres away. In the thick of it, yet worlds apart. Around us, violence is mounting. Gaza under daily heavy bombing. Settlers terrorise the West Bank with impunity. Palestinian school children and workers harassed in the city. The sound of fighter jets a constant, vile presence. Horrid scenes from the misfired Hamas rocket at Al Ahli hospital. The mendacious rhetoric of rooting out Hamas while sparing civilians, parroted by unknowing or uncaring governments worldwide. Only the first indications of an engulfing humanitarian abyss.

I never was much of a sleeper. But this is my first encounter with genuine insomnia. Only in hindsight do I understand the effects of extended sleep deprivation. The difference between sleep and dozing off, as the body and mind simply shuts down in irregular intervals. In lieu of repose, sleep invades my waking hours, dulling senses and emotions: a contour-less limbo of absent presence. The rooster crowing at 3 becomes a welcome herald of daylight, a release from futile efforts at nightly rest.

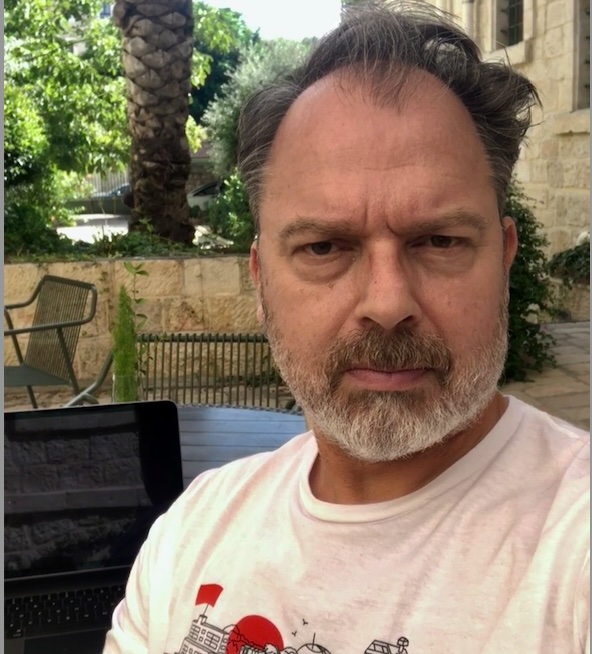

Left: ‘Safe’ and sleep-deprived in the STI garden, 12 October 2023.

Right: Frog-emoji-safety-family-ritual. On 11 November I had dozed of and missed a posting.

Curiously, sleep deprivation affects distraction more than concentration: what becomes impossible is rest and respite. Any attempt at solace slips through my fingers, magnetically drawn to the next click on the next news flash, the next entry in the diary. Fiction, series, football games are defenceless against the foggy wandering of an insomniac mind. I find focus only in three activities: work, cooking and exercise. Ironically, I have seldom been more productive in writing, attentive to couscous and lentils, faster up and down the vicious slopes.

Perhaps the human mind is unable to stay in emergency. Agamben’s state of exception of the repressive state becomes a personal state of mind. Rage, fear, frustration and sorrow persist, but as accustomed everyday reality. Or perhaps I am just worn out? Whatever the reason, by the end of October my attention increasingly gravitates back to my project and fieldwork.

I roam a city strangely the same, only more so. More units are policing the perimeter of the Eastern city. All gatherings are banned. A group of elderly praying men outside the meat market are roughly shooed away. In the streets people are quiet, hurrying along with downcast gaze. More Palestinian store fronts are shut closed. Some in strike, other in economic desperation in a city bereft of tourist and pilgrims. The busy alleys of the Old City have transmuted into ghostly corridors of anxious inertia. A few steps away from the public paths, however, chat and laughter prevail. A visit to a barber engages the entire salon of middle-aged and elderly men in intense discussion around my chair. Not about bombings and suffering. About football. Wherever did Ibrahimovic go? About missing the Palestinian national team. Oh, and remember the airport?! The port! A barbershop conversation like any other, anywhere. And still not.

The Western city, in contrast, slowly wakes up to bustling street life. Here too the atmosphere is alert, yet strikingly warm. Omnipresent officers are chatting with pedestrians, joking with children, mounting a toddler on a Police horse, allowing selfies. The coffee shop across Beit Tabor is closed. A note on the door: ‘Out for the day. Going to serve our brothers in the IDF’. On Zion Square, crowds gather around musicians playing Israeli evergreens, singing along. Stickers embellish storefronts: Yachad ninatze’ach, together we shall win. Buildings, benches, bus stops are plastered with Bring Them Home-posters. Safra Square by City Hall is staging manifestation after manifestation of frustration, anger, fear and solace for the hostages. Layers upon layers of urban memory created and recreated day by day. And everywhere blue-and-white flags. Flags covering buildings, flags in windows, flags projected on City Walls, flags flying from cars.

In the same vein, my work remains identical, still oddly transformed. More than conducting research I feel increasingly conducted by a field unfolding in front of me. Museums, monuments, places of memory move along familiar paths, yet ignited with new momentum, deepened layers of significance and affect. Spaces saturated with an ambiguous ambience of stillness and rupture, of comfort and violence.

I stroll around the Holy Sepulchre in solitude, a space normally thronged by endless queues, allowing but a fleeting glance. Uninterrupted, I stand alone in stillness by the grave, with a candle lit for dad. The Museum of Islamic Arts is closed. Of little surprise, perhaps. I am no less astounded to find its wall covered by an enormous billboard, displaying faces of the hostages. If this city ever had room for subtlety, it vanished utterly on October 7.

The Museum of Underground Prisoners, commemorating the Jewish para-military groups resisting the British Governate, is also closed. Still the helpful staff grant me a private visit and guided tour. I stand frozen in the workshop arranged for the crafts of visiting school children, instructed to engrave plaster plates with the insignia of para-military organisations. A messy assemblage of memory and material pottering, of sketches, plaster dust and symbols of Haganah, Palmach, Betar, Irgun, Lehi. No one has touched this room since Friday evening, October 6. A time capsule in double-exposure of innocence and violence.

Mercifully, the Tower of David Museum remains open: the newly re-organised official city museum, one of my key-cases of Israeli local memory. Since my third visit, the receptionists have begun to engage me in conversation. Visitors remain sparse, but on the night of November 13 the courtyard fills up for a sing-along. Enthusiastically but shyly, visitors join the two-hour-collar of feelgood ballads from the Israeli song book: Ofra Haza, Haim Mosche, Zohar Argov, Gali Atari, Naomi Shemer… All concluding with the traditional Acheinu kol beit Yisrael: Our brothers, the whole House of Israel.

‘Do you do this often’ I ask in the reception. ‘Oh no. This is special. Only on Memorial Day…’

Song Night at Tower of David Museum, singing along in ‘Yakhad’(Together, 1995) by Gali Atari, who was part of Milk and Honey, the 1979 winners of Eurovision with ‘Hallelujah’. Video recording, 13 November 2023.

By Hanukkah, my time in the city draws to a close. I am tense: torn between relief and a menacing feeling of betrayal. Already dreading the ‘How was it?’ of friends and colleagues. Not only am I uneasy with the unavoidable question as such, its social nicety. I literally do not know. I have not even begun to ponder it. All know is that I am exploding with impressions. That I sit on a mountain of material. That I do not sleep. That it is a question I ultimately need to ask myself. I ask Anna how she does it. ‘I don’t’, she says. ‘And I talk with people who also don’t.’

A journey to Al-Quds, Yerushalaim, Jerusalem never begins on the day of travel, nor ends with one’s return. Personal memories are pre-scribed by and inscribed with events unfolding around us, in Palestine, Israel, the Middle East, the world. The recollections of my autumn in the city are sifted through a spring of catastrophe, as the atrocities in Gaza has mounted to new extremes. Events in our immediate surroundings interconnect here and there, then and now. Exception presses upon us.

The Eurovision spectacle in Malmö becomes world politics, turning streets into a rallying point for humanitarian engagement, as well as an exceptional display of urban securitization under hovering police drones, helicopters and snipers. The student encampment of ‘Palestinagård’ transforms the Lund University campus into a space of resistance, until violently rooted out to make way for the hallowed doctoral conferment procession, with its cannon salutes…

It takes until March before I begin to look for words, attempting to articulate experience in memory and reflection. I find unexpected relief in teaching, when Andreas Westergren asks me to give a talk for the MA students of CTR. By framing the matter methodologically, by deliberately taking distance, formulating a series of problems rather than answers, I find a way in. I call my talk ‘Sleepless in al- Quds: four field paradoxes pre/post 7.10’. It becomes a template for eventually writing this text, guided by four acknowledgements:

- nothing will ever be the same; everything is just the same (only more so)

- in the thick of it; in a world apart

- in an everyday state in a state of exception

- the impossibilities of representation versus our commitment to representation.

‘Are you sleeping better now’, a student asks. I smile at this unexpected question. ‘Honestly? So-so’. ‘Will you go back?’ That one is easier. ‘As soon as I get the chance.’

Torsten Janson